Desire Paths

Before the 20th century, nearly every city ever built was a co-creation of its own residents. A neighborhood, as it grew, would be shaped by many hands. What started as a row of pop-up shacks might, over a generation, become a Main Street of brick and stone structures occupied by local merchants who lived in apartments above their shops. Another generation later, 5-story hotels and apartments might have risen. People often adapted buildings freely: putting on an addition or a second story, carving out an in-law unit or subdividing into a duplex. A healthy neighborhood would be constantly evolving and regenerating itself.

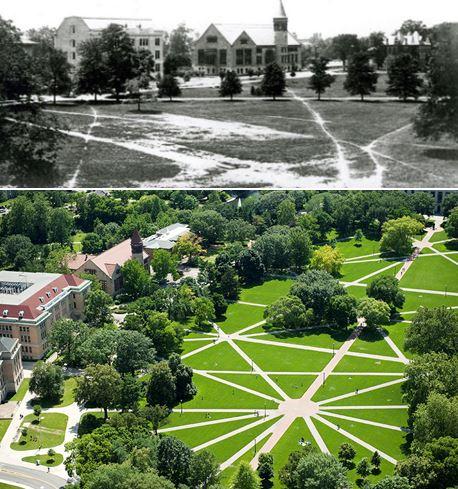

Desire paths are created by the erosion from human or animal foot traffic, usually indicating the most efficient path from point A to B. These paths don’t necessarily follow the paved paths already laid out. The Oval walkways at Ohio State University were paved based on the students’ desire paths. How did they do this, exactly? To map out the paths, the planners waited for it to snow, went up in a hot air balloon and made notes.

If we don’t want cataclysmic change in our cities, then we need to tolerate gradual change. Everywhere.

We need to support our communities’ desire paths.

Our cities used to have thriving ecosystems of incremental developers, though not all of them would have used that term—being a “developer” didn’t mean what it means today. The person building next door to you was more likely to be your neighbor, and far less likely to be a corporation headquartered far away. And this meant that they had an interest in cultivating a successful place for the long haul, not merely extracting a short-term profit.

The steady stream of gradual money from this sort of development results in neighborhoods that are not static, but ever-churning places that can sustain virtuous cycles of growth and reinvestment. They are built in response to the immediate needs of their residents. They build wealth for their inhabitants, even those who start with next to nothing. And they are places where complex, rich communities can take deep root, even as they grow and flex to let more people in. As Charles Marohn writes in Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity:

It is critical that every neighborhood … be allowed, by right, to evolve to the next level of development intensity … without any special permitting, approval of neighbours, or added conditions.

A much larger majority of places are seeing virtually no growth or physical transformation. These “no-build zones” have expanded to cover most of residential America. They include, on the one hand, affluent enclaves where everything from zoning codes to parking standards and HOA rules are designed to shore up exclusivity and keep out those who can’t pay the cost of entry. But they also include growing swaths of concentrated poverty and decline: places that could benefit from reinvestment but where only a downward spiral of decay and abandonment appears to be on the menu. As a example of this stark dichotomy, in Cuyahoga County, Ohio—an area of 1.2 million people that includes the city of Cleveland—75% of new homes built from 2014 to 2018 were built in just 5% of neighborhoods.

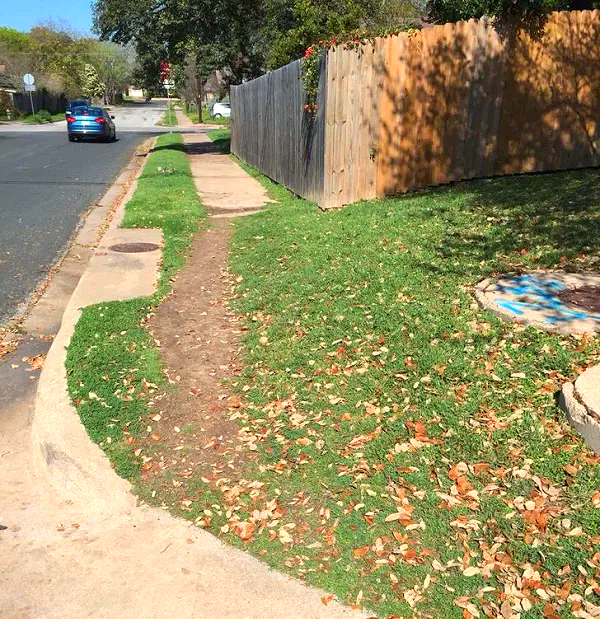

If you own a house and want to make it a duplex, for example, you should be able to walk into City Hall and walk out with a permit to do so. If that can never happen, then natural growth along “desire paths” is thwarted. Pressure builds in the few pockets that allow for growth. This drives up prices.

Don’t ignore desire paths, otherwise you have cut off the sidewalk, and your citizens still need to get where they need to go.

We need to retool our regulatory processes and financing systems to legalize small. Right now, convoluted zoning and development rules, long and uncertain approval processes, and financing mechanisms that favor predictability and standardization have left few who can afford to be in the game. This precludes many citizens from playing a meaningful role in co-creating the places they will live. And it is at the root of America’s overlapping housing and affordability crises.